Introduction to Saddle Fitting

Good Saddle Fit from the Start

Trees, Panels, and Motion

Saddle Fitting and Panel Design

Saddle Trees

More About Saddle Trees

Custom Saddle Fit. What Does it Mean?

The whole load-bearing structure inside the saddle has a shape and the horse’s entire back has a shape, which changes in different phases of motion. Horses of various shapes require trees of different shapes. It’s not sufficient to use the same tree in multiple widths to fit every horse. From a manufacturing standpoint, the truth of this statement is somewhat inconvenient.

On the whole, the industry does little to discourage the broadly held notion that there is a blueprint of measurements that applies across the board (this horse is a wide — this tree is a medium), but in reality horse shapes and tree shapes are much more complicated than that. To begin with, the whole shape of the tree has to fit, not just the head. But only the head measurement is even nominally considered in the customary M, MW, W designation. This actually provides no vital information about the shape of the tree. Is it medium and flat or medium and curvy? How steeply do the rails descend from the head? How long are the tree points? And what exactly is medium in this case? Like shades of color or relative dimensions, there is no absolute standard. Each particular tree has its own fit considerations, so wide or medium is entirely relative to the tree in question.

In truth, we have not developed a very useful lexicon for describing tree shape. Using a single-word designation to describe either a tree or a horse is pointless because they are three dimensional. A particular tree, depending on its shape, might fit wide at the head but narrow at the neck. How should it be described? A horse might be steep and narrow right behind the shoulder but wide and flat three inches further back at the base of the withers. Is he narrow or is he wide? What single “size-word” would you use to describe a woman with a 26” waist and 44” hips (other than pear-shaped)?

Describing a saddle by centimeter measurements is about as helpful as describing it as black. Please do not assume that a larger number means a wider fit. If you chopped off the ends of the tree points on a 36 cm tree so that the spread between them was 32 cm, without altering any angles on the head, the saddle would fit considerably wider at the head, even though it would have a narrower absolute distance between the points. In other words, if the arms of the tree are longer, it will fit narrower, even if the absolute distance between the tree points is greater, which would mean it’s technically wider since it would be, say, a 36 cm tree with long arms as opposed to a 32 cm tree with short arms. Some companies (generally European) use these numeric designations for trees, but they are only meaningful (which is being kind) if you are comparing trees that are otherwise identical. Clearly one cannot encapsulate all relevant information about the fit of a tree in a single word, but that’s the blueprint the industry puts forward and it’s the standard that most consumers accept as credible.

There are many factors that can affect whether a particular saddle remains stable on the horse through the horse’s full range of motion, but the first questions to ask are: Does the whole shape of the tree inside this saddle conform well in all its dimensions to the shape of this horse’s back? Does it have enough “tolerance” in its dimensions that it is unlikely to grab, crush, or pinch the horse as the horse’s back changes continually in various gaits and movements?

The saddle tree is a very basic, simple, somewhat crude piece of technology that is required to perform a very complex function. In theory, it should be easy to tell whether the load-bearing structure contained within the saddle is or isn’t a good match in shape for the horse it is used on. In reality — not so easy. To begin with, once a saddle has been built around the tree, it requires some expertise or familiarity with a particular tree to discern its shape or dimensions accurately, except at the tree points. In practice, most of us tend to focus on what can be more readily assessed from the outside when we’re evaluating saddles, including the angle of the tree points, the wither clearance, the balance of the saddles, and the panels, which are the cushions of wool or foam that separate the tree from the horse. And, of course, whatever the rest of the seven deadly points of saddle fitting are.

Much attention is paid to the depth, shape, angle, or spacing of the panels, and it is certainly true that a well-designed panel can enhance the fit of an appropriate tree. A good panel with plenty of interior volume can be a marvelous instrument for fine-tuning the balance the saddle, and providing a close, stable purchase between the saddle and the horse’s back. But, the load-bearing structure of the saddle is the tree rather than the cushion it sits on. Even a superb panel cannot compensate adequately for a serious mismatch between tree and horse. Contrary to popular belief and practice, if the tree is not a good match for a horse in its entire shape, you cannot “refit” the saddle successfully by altering the wool flocking in the panels, or replacing foam panels with wool panels, or even by forcing the points wider or narrower.

The purpose of the tree is to distribute the rider’s weight as evenly as possible over the broad, strong, muscular surface of the horse’s back. The tree is also designed to protect the crucially sensitive spine and central nervous system from impact. In a nutshell, it’s there for damage control. Like shoes for humans, some trees are more “forgiving” in their shape, more versatile to fit, and a bit more tolerant of minor changes in the horse’s condition. These types of trees would be comparable to sensible, functional walking shoes one would wear for a long journey. Unfortunately, in the opinion of this writer, there has been something of a trend in recent years toward designing a good number of saddles on trees that are ergonomically bliss for riders but may be less than generous in fitting certain types of horses.

The purpose of the tree is to distribute the rider’s weight as evenly as possible over the broad, strong, muscular surface of the horse’s back. The tree is also designed to protect the crucially sensitive spine and central nervous system from impact. In a nutshell, it’s there for damage control. Like shoes for humans, some trees are more “forgiving” in their shape, more versatile to fit, and a bit more tolerant of minor changes in the horse’s condition. These types of trees would be comparable to sensible, functional walking shoes one would wear for a long journey. Unfortunately, in the opinion of this writer, there has been something of a trend in recent years toward designing a good number of saddles on trees that are ergonomically bliss for riders but may be less than generous in fitting certain types of horses.

A tree that fits poorly anywhere can end up causing more damage than it prevents, so it cannot be stressed too much that the entire shape of the tree is critical to good fit, not just the tree’s nominal width or size. Nor is it possible to obtain consistently accurate solutions by “adjusting” a tree; nor are conventionally interchangeable head plates (which some people call gullet plates) any sort of a panacea. Unfortunately, matching one complex shape to another is not that simple, though a massive amount of marketing has succeeded to some extent in convincing many riders that it is that simple. In order to achieve correct balance for the rider and even distribution of weight for the horse, the tree must be the correct width, and of vital importance, the tree must also be the correct shape for the horse.

It is critical to grasp that:

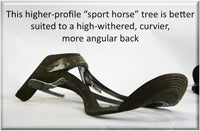

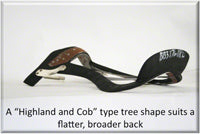

Among other critical fit considerations that are often ignored are the shape of the head, its horizontal diameter, the length of the tree points, the angle and spacing on the rails, and whether the front-to-back shape of the rails is flat or curvy.

There are many types of trees on the market, and a tree that may seem quite suitable by the obvious criteria of adequate wither clearance and a level seat may be very unsuitable and painful to the horse in some less obvious aspect of fit that might not be taken into consideration. Many riders on wide horses — or horses who are fairly thick at the base of the withers where the stirrup bars lie — want very much to avoid having to adapt themselves to the full width of the horse they are riding. There are many, many saddles on offer to facilitate them in this avoidance, at least until the consequences to the horse kick in. What complicates this situation is that such saddles may appear superficially to be a reasonably good fit. It is not always easy to identify underlying problems with the shape of a tree once the tree is covered by a seat on top and a thick panel below. This is why we feel it is so important to have a clear understanding of the fit considerations of a particular type of tree and whether it is suitable in all of its dimensions for a particular type of horse.

Many riders on wide horses — or horses who are fairly thick at the base of the withers where the stirrup bars lie — want very much to avoid having to adapt themselves to the full width of the horse they are riding. There are many, many saddles on offer to facilitate them in this avoidance, at least until the consequences to the horse kick in. What complicates this situation is that such saddles may appear superficially to be a reasonably good fit. It is not always easy to identify underlying problems with the shape of a tree once the tree is covered by a seat on top and a thick panel below. This is why we feel it is so important to have a clear understanding of the fit considerations of a particular type of tree and whether it is suitable in all of its dimensions for a particular type of horse.

It is immensely helpful if the fitter has some familiarity with the overall shape and dimensions of the particular tree in question to be confident that the structural contours of the tree are a close match for the contours of the horse’s body. Again, it is analogous to fitting a running shoe. If the length and width are perfect for the athlete’s foot, then by all superficial measures the shoe appears to fit. But any specialist in sports medicine will confirm that an athlete who persists in wearing shoes that are unsuitable in other, less obvious ways likely at some point to become a major underwriter of an orthopedic surgeon’s golf club membership.

It is immensely helpful if the fitter has some familiarity with the overall shape and dimensions of the particular tree in question to be confident that the structural contours of the tree are a close match for the contours of the horse’s body. Again, it is analogous to fitting a running shoe. If the length and width are perfect for the athlete’s foot, then by all superficial measures the shoe appears to fit. But any specialist in sports medicine will confirm that an athlete who persists in wearing shoes that are unsuitable in other, less obvious ways likely at some point to become a major underwriter of an orthopedic surgeon’s golf club membership.

One aspect of tree fit that is relatively easy to assess is whether the tree points are a reasonable match for the angle of the horse’s shoulder, and often the investigation delves no deeper than this. What is harder to discern is whether the other dimensions of the tree are equally well-matched to the shape of the horse’s body.

If, for example, the space between the rails of the tree is too narrow for a horse with a short, dome-shaped wither, the saddle will pinch and pivot over the stirrup bars. One clue to this might be that the back of the saddle tends to flip up and down in rising trot. In this instance, if the spacing of the rails is too narrow or angular for the width and spread of a particular horse’s back, the narrow area under the stirrup bars forms a sort of stricture where the contour of the tree deviates significantly from the contour of the horse’s back. As the rider weights the stirrup bars, this becomes like a fulcrum, levering the back of the saddle up and down when the horse is in motion. The visual effect may be somewhat disguised either by thick gusseted panels or by trying to level the back panels with a riser pad, but nothing can compensate for the underlying problem of a tree whose shape is a poor match for the horse under the stirrup bars, even if it the fit appears to be a fine through the tree points.

Another confusing factor in making a visual assessment of the shape of a tree inside a saddle is that the spacing of the panels frequently obscures the features of the tree and can in some instances give a misleading impression of how wide or narrow the spacing is between the rails. Just because there is a generous channel or spacing between the panels, it should not be assumed that this mirrors a tree with similarly generous ease in its angles and proportions.

What is crucial in making an evaluation about the suitability of fit is not really whether the saddle looks like a good fit when the horse is standing in the cross ties, but what happens between saddle and horse when the horse is in motion under a rider. The saddle must be stable and well balanced through the entire range of equine biodynamics in order to perform its two critical functions of protecting the spine and distributing the rider’s weight comfortably and evenly.

It is frustratingly difficult to get accurate information about the shape and dimensions of a tree that has a saddle already built around it, but understanding the fundamental fit considerations of the tree inside a particular saddle will go a long way in reducing the random trial and error that many riders slog through in shopping for a saddle. In all likelihood, if consumers had more specific knowledge of trees and were more assertive in seeking specific information about the tree in any saddle they were considering, the industry would eventually be compelled reveal more specific shape attributes of the trees they are using, and provide us a wider range of genuine choice. This is what has happened in the running shoe industry, which now offers many specialty fits for a wide range of feet. Our horses are no less deserving of a wider, better range of tree choices, but this will happen only if people who buy saddles are sufficiently well-informed about trees that they demand better fit solutions.

Introduction to Saddle Fitting

Good Saddle Fit from the Start

Trees, Panels, and Motion

Saddle Fitting and Panel Design

Saddle Trees

More About Saddle Trees

Custom Saddle Fit. What Does it Mean?